Is social media making us antisocial?

(You can suggest changes to this post.)

I’ve noticed a concerning trend over the last few years, and I’m not exactly sure what to do about it. As a culture, our communication habits are changing, and the results may be terrible for our mental health.

This is a long post, and it’s going to help if we start with a brief review of communication over the ages, beginning with face-to-face interactions. These provide plenty of non-verbal signals, such as body language and vocal tone. It’s often clear when interacting with someone if they’re paying attention or distracted; if they’re angry, joking, happy, or just bored. (Although even face-to-face, we’re still good at getting things wrong).

At some point we learned how to read and write, and while letters were an important stage in our development, I’m restricting myself to looking at direct and instantaneous communication in this article.

Skip forward a few thousand years to the telephone. This technology was game-changing. It allowed people to talk, even when separated by distance. While it wasn’t possible to read body language over the telephone, one could still read vocal tone. Telephones were a fixture in people’s homes, so you generally knew you had someone’s full attention when you were talking to them, and it became rapidly apparent when you did not.

With the advent of computers, things became more interesting, and definitely more diverse. were find ourselves with IRC, chatrooms, SMS, instant messenger, and a variety of other text-based communication forms. These provided fewer non-verbal signals (emoticons are a notable exception here), along with less clues for when someone was distracted with other things or not. But still, one used these forms of communication to maintain a conversation with an individual, or a directed group of people.

The dominant mode of communication with social media is 'post-and-hope'.

But now we’re seeing a form of communication which is radically different from what we’ve experienced in the past: social media. The dominant mode of communication with social media is the undirected broadcast, what I call “post-and-hope”. You post on your wall, or tweet to the world, and people may respond, or they may not. When they do respond, the responses are more ephemeral. It’s harder to have a personal conversation when all six-hundred of your friends are watching it, or you’re limited to 140 characters.

Social media doesn’t preclude more directed conversations, but it is shifting the ways in which we’re communicating. Combined with the rapid uptake of mobile electronics, where a friend being ‘online’ may simply mean they’ve opened their phone for a few seconds in an elevator, there’s even more uncertainty associated with directed conversations than ever before.

The result is that for many people, a significant amount of communication is broadcasted, rather than directed, and the continuity of a conversation is more unpredictable, and more likely to evaporate without a clear verbal or textual signal (such as “catch you later”), than ever before.

I’m aware that “all this technology is making us antisocial” is hardly a new sentiment. My parents expressed concern about me hanging out on bulletin boards with ‘electronic people’ as a teenager, even though I viewed that as exceptionally good for my social and intellectual development.

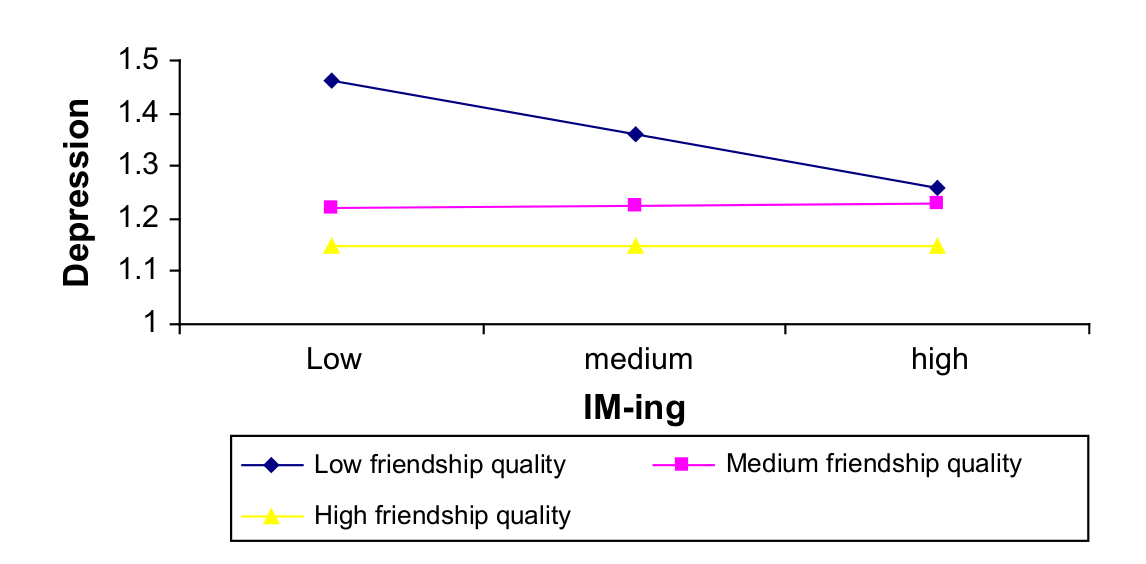

While the scientific literature shows that spending time on instant messenger is protective of mental health if one is feeling socially isolated¹, studies into social media itself seem to be less clear, and I’m still trying to make sense of them. I’ve included references at the bottom of the article, in case you wish to do some reading yourself.

However this is a personal post, and one thing I’m concerned about is the trends in my own social habits. I communicate with many more people than I used to, but I’m much less close to any of them.

I communicate with many more people, but I'm less close to any of them.

Go back five years ago, and I have a small number of close friends whom I felt very comfortable talking to, and we would share our experiences and thoughts extensively. While we weren’t in constant contact, it was very reassuring to know they existed, and I took for granted that if I was worried or anxious, or wanted to share news of a success or receive guidance on some defeat, that I’d have close friends to fall back on.

Now, things feel different. My close friends are still my friends, but communicate with them less. When I do communicate, the conversations are more shallow. I’ve noticed that’s often my fault; I’m less likely to have an on-line conversation as a dedicated activity, and they seem to more often start as side-effects from other social media use, and dry up just as quickly.

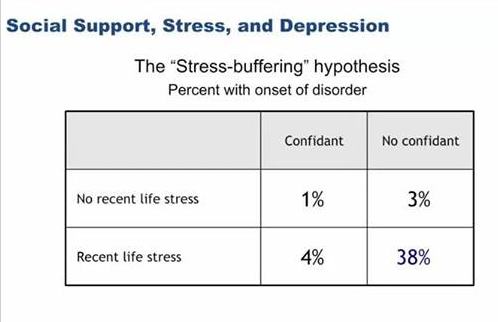

That worries me, not just from a social standpoint, but also from a mental health one. We know that having a confidant—someone with whom one feels they can talk to about anything—is hugely protective to one’s mental health. If social media is making us less close, then we run the risk of many more people suffering from mental health issues due to that isolation.

I’m sure part of the reason for these changes is the sheer number of people with whom I interact with on-line. If you were to go back a decade ago, I had dozens of people in my instant messenger contact list. Today, my Facebook friends number in the hundreds.

I don’t yet have enough evidence to say that this is becoming an issue for society in general, but I’m concerned that it might be. There’s a number of studies showing links between social media usage and depression, but these don’t show causality; people feeling isolated may be using social media more as a means of support. That’s certainly something I’ve done in the past.

What’s just as concerning for me—if not more so—is that that systems like Facebook are increasingly taking the choice of which stories to display on one’s feed out of the user’s control, and are instead selecting what they feel will provide you with the best ‘personalized feed’. That’s generally understood to be whatever causes you to continue to interact with Facebook, since that means you’ll view the most ads. However it opens the possibly of algorithmic isolation, simply because your important posts may not be shown to others.

Facebook is particularly notable for burying posts where the author expresses that they’re sad or unhappy. That’s not a deliberate decision on Facebook’s behalf, but nobody ‘likes’ their friend being unhappy, and many people don’t know what to say in the comments. To Facebook, a sad post looks like a boring post, because nobody’s interacting with it. I’ve found that adding “Likes=Hugs” to the top of my writing is sometimes enough to overcome this, but it’s rare that a post about one feeling sad can compete with a picture of a cat.

Still, it seems that every new form of communication is heralded as being bad for our mental health soon after it’s introduced, and often those fears end up being unfounded. Social media and its associated modes of communication are still very young, and while they’re an active topic of study, it may still be some time until we truly understand their impact on society and individuals.

In the meantime, you can subscribe to me on Facebook here.

References and further reading

¹ Selfhout, Maarten H.W., Susan J.T. Branje, M. Delsing, Tom F.M. ter Bogt, and Wim H.J. Meeus. “Different Types of Internet Use, Depression, and Social Anxiety: The Role of Perceived Friendship Quality.” Journal of Adolescence 32, no. 4 (August 2009): 819–833. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.011.

² Eaton et al, “Major Depression in the Population: A Public Health Approach”

Moreno, Megan A., Lauren A. Jelenchick, Katie G. Egan, Elizabeth Cox, Henry Young, Kerry E. Gannon, and Tara Becker. “Feeling Bad on Facebook: Depression Disclosures by College Students on a Social Networking Site.” Depression and Anxiety 28, no. 6 (2011): 447–455.

O’Keeffe, G. S., K. Clarke-Pearson, and Council on Communications and Media. “The Impact of Social Media on Children, Adolescents, and Families.” PEDIATRICS 127, no. 4 (March 28, 2011): 800–804. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0054.

Valenzuela, Sebastián, Namsu Park, and Kerk F. Kee. “Is There Social Capital in a Social Network Site?: Facebook Use and College Students’ Life Satisfaction, Trust, and Participation.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14, no. 4 (2009): 875–901.

3 Myths That Block Progress For The Poor

The belief that the world can’t solve extreme poverty and disease isn’t just mistaken. It is harmful. Read more...

This site is ad-free, and all text, style, and code may be re-used under

a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.

If like what I do, please consider

supporting me on Patreon,

or donating via Bitcoin (1P9iGHMiQwRrnZuA6USp5PNSuJrEcH411f).

This site is ad-free, and all text, style, and code may be re-used under

a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license.

If like what I do, please consider

supporting me on Patreon,

or donating via Bitcoin (1P9iGHMiQwRrnZuA6USp5PNSuJrEcH411f).